Battle of the River Plate Commemorative Service

I begin by greeting everyone in the languages of the realm of New Zealand, in English, Māori, Cook Island Māori, Niuean, Tokelauan and New Zealand Sign Language. Greetings, Kia Ora, Kia Orana, Fakalofa Lahi Atu, Taloha Ni, and as it is morning [sign].

I then specifically greet you: Rear Admiral Anthony Parr, Chief of Navy; Hon Christopher Finlayson, Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage; Military and Diplomatic Representatives, the latter including Your Excellency Thomas Meister, Ambassador for the Federal Republic of Germany and Your Excellency, Alberto Fajardo, Ambassador of Uruguay; Air Vice Marshal (Rtd) Robin Klitscher, National President of the Royal NZ Returned and Services’ Association; River Plate Veterans and your families, Chaplain Bob Peters; Distinguished guests otherwise; Ladies and Gentlemen.

Thank you for the invitation to address this service, which is one of a number of events occurring in New Zealand to mark the 70th Anniversary of the Battle of the River Plate. As Rear Admiral Parr has spoken of the significance of the battle to the Royal New Zealand Navy, I would like to take an opportunity to speak of the context of the battle and its importance more generally for our country.

The Battle of the River Plate occurred just three-and-a-half months after the Nazi attack on Poland on 1 August 1939 that had precipitated the Second World War. That War has been, to date, the single greatest conflict to engulf the world and claimed the lives of some 50 million people, including that of one in every 150 New Zealanders.

The last weeks of 1939, seventy years ago, were a dark and uncertain time. Poland had been quickly divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union following September and Japan and China were locked in an ongoing war. The United States was neutral and France, Britain and the Commonwealth stood alone.

New Zealand had pledged to send forces to Britain’s aid and three echelons of troops, which were to depart in January 1940, were being made ready. However, their safety on the long sea voyage, and the security of New Zealand’s trade was threatened by vessels such as the Deutschland Class Cruiser or “pocket battleship”, the Admiral Graf Spee. The Graf Spee, operating in the Southern Ocean and Atlantic, had already destroyed several merchant ships including the Doric Star, which was heading to Britain from New Zealand, laden with frozen meat, dairy produce, and wool and had been intercepted in the Eastern Southern Atlantic Ocean, off South Africa.

Public morale had also been dented by the loss to U-boats of the aircraft carrier HMS Courageous off the coast of Ireland and the battleship HMS Royal Oak, which had been sunk audaciously whilst at anchor in Scapa Flow in Scotland with great loss of life.

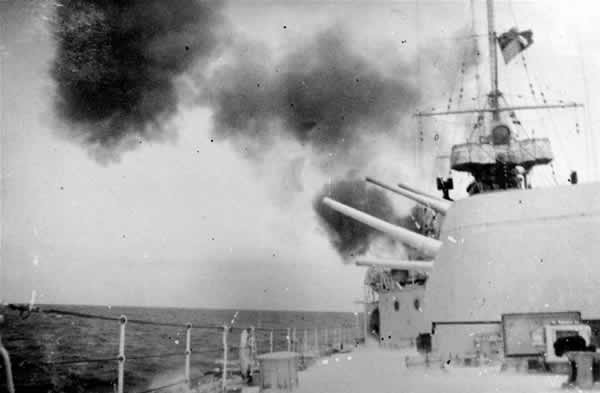

It was in this bleak period and setting that, at 6.18am, 70 years ago tomorrow, in the waters off the coast of Argentina and Uruguay, the Admiral Graf Spee commenced fire on the cruiser HMS Exeter and the light cruisers, HMS Ajax, and her sister ship, the New Zealand manned vessel, the HMS Achilles.

At first glance, three against one might seem an uneven match. Although the Graf Spee’s size was limited by international treaties to that of being a cruiser, she was as heavily armed as a battleship. The firepower at the disposal of the British commander, Commodore Henry Harwood, was equivalent in effective terms to the Graf Spee’s secondary armament.

The Graf Spee concentrated its attention on the Exeter, whose 8 inch guns were a greater threat. Exeter suffered severe damage, but before Graf Spee could finish her off, her fire was drawn by Ajax and Achilles with their 6 inch guns.

The action lasted just 82 minutes. The Graf Spee’s master, Captain Hans Langsdorff, then chose to take refuge in the neutral port of Montevideo, Uruguay where he later scuttled the Graf Spee rather than face the superior force he incorrectly believed was waiting for him in Atlantic waters.

Several features make what was later called the Battle of the River Plate stand out. It was the first major naval battle of the Second World War. Against odds, the Allied side was victorious and it was a much needed boost to public morale.

It was also a victory in which New Zealand seafarers played a significant role. On return to Auckland in February 1940, the Achilles and its crew received a welcome for heroes. It is estimated 100,000 people lined Queen Street as the crew marched from the waterfront to the Town Hall for a civic reception.

The pride which New Zealanders felt was boosted by a message to the New Zealand Naval Board by the British Squadron Commander, Commodore Harwood, who said: “The Achilles was handled perfectly by her captain and fought magnificently by her captain, officers and ship's company.” He added that he fully concurred with comments made by the Achilles Captain Edward Parry that “New Zealand has every reason to be proud of her seamen during their baptism of fire.”

A further feature of the battle is that whilst the British ships lacked the firepower to seriously damage the Graf Spee, that in no way stopped them from taking her on. In this regard, Achilles' motto, in Latin, Fortiter in Re or, in English, "Unyielding in Action" describes well the approach that was taken. In overall terms, the general significance of the Battle is well put by contemporary historian Ian McGibbon in this way:

“The immediate outcome of the battle gave the Admiralty much satisfaction. A major threat to Atlantic shipping had been removed, a powerful German warship was destroyed, and many Royal Navy ships could now be released to other duties. But the psychological and moral impact was even more important than its material outcome. The British victory gave a huge boost to Commonwealth morale. It was the first bloody nose inflicted on the Germans and the Achilles role was a special source of pride to New Zealanders.”

A number made the ultimate sacrifice in the service of their nation and for the democratic values we cherish. At this time, it is appropriate to specifically acknowledge the Achilles’ veterans who are present here today: Bob Batt, Graham Bennett, Vince McGlone, Eddie Telford, Albert Evans and Arthur Hunt. I join everyone here in thanking you for your service.

On the Allied ships, the lives of 72 officers and ratings were lost, with a further 47 wounded, including four deaths and nine injuries on Achilles. On the Graf Spee, 37 men died and a further 57 were injured.

Seventy years later we recall and recognise the bravery and honour of those who died on both sides. The presence here today of the Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany is a recognition that people who were once enemies are now friends. It is in that spirit of friendship that we reaffirm a commitment to seeking peaceful ways of resolving disputes among nations.

And on that note, I will close in New Zealand’s first language offering everyone greetings and wishing you all good health and fortitude in your endeavours. No reira, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, kia ora, kia kaha, tēnā koutou katoa.

For more information, visit the RNZN Museum website here or the NZ History website here

Read the history of the Battle in the Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War here