Alexander Turnbull Library 90th Birthday Celebrations

I begin by greeting everyone in the languages of the realm of New Zealand, in English, Māori, Cook Island Māori, Niuean, Tokelauan and New Zealand Sign Language. Greetings, Kia Ora, Kia Orana, Fakalofa Lahi Atu, Taloha Ni and as it is the evening (Sign)

I then specifically greet you: Hon Nathan Guy, Minister responsible for the National Library of New Zealand; Penny Carnaby, National Librarian, and Chris Szekely, Chief Librarian of the Alexander Turnbull Library; Professor Raewyn Dalziel, Professor Mark Apperley, Dr Elizabeth Caffin and Dr Monty Soutar, Kaitiaki of the Alexander Turnbull Library; Rachel Underwood, President of the Friends of the Turnbull Library and your executive members; Your Excellencies Paul O’Sullivan High Commissioner for Australia to New Zealand; Justice MPH Rubin, High Commissioner for Singapore to New Zealand, and Vicki Treadell, High Commissioner for the United Kingdom to New Zealand; Grant Robertson and Gareth Hughes, Members of Parliament; Distinguished Guests otherwise; Ladies and Gentlemen.

Thank you for inviting my wife Susan and me to this event marking the 90th birthday of the establishment of the Alexander Turnbull Library.

I have been asked to give the Founder’s Lecture and I thus join a list of Governors-General who have spoken to the Friends, starting at least as long ago as 1958, with my predecessor, Viscount Cobham who spoke in that year about family manuscripts. More recently, I see that Archbishop Sir Paul Reeves, Dame Catherine Tizard and Sir Michael Hardie-Boys have either spoken at meetings of the Friends or have given the Lecture.

In my contribution, I would like to speak of the role of the Turnbull, as a library and as a national institution. I will approach this first by examining my own connections with books and libraries, before turning to Turnbull’s gift and its significance 90 years after the library he founded, was opened.

In every New Zealand setting, whoever speaks should first establish a place to stand before the audience. In this regard, I speak first as the current Governor-General, a role that I have been privileged to enjoy with my wife, Susan, for almost four years, and as an erstwhile lawyer, Judge and Ombudsman. I do not claim any specialist expertise in libraries, librarianship or in the wider discipline of information management.

I do, however, claim a life-long love of books. Reading has been a central part of my life since the time of being a small boy in Ponsonby, Auckland when my membership of the Leys Institute Library at the Three Lamps stood alongside having a Post Office Savings Book. To this day I am almost always reading books, as is Susan, that notion being one we have shared. We inculcated reading into our family’s life and continue membership today of more than one book group. As Governor-General, whenever visiting schools, I have consistently spoken to children about both the joys and importance of reading for one’s individual prospects and for the progress of the wider community.

It will not, therefore, be any surprise to hear I have been, through my life, a constant visitor to, and a supporter of, libraries. That has always been for a mixture of pleasure, study and research—first as a school and university student, then as lawyer, Judge, Ombudsman and Governor-General but also just as a “goer to”. I must confess though to being one of those library-goers whose initial goal has often been modified. This is so because inside the library, time and again, I continue to be one who turns to adjectival and unnecessary things before undertaking the task in hand.

By constitutional convention, the Head of State and his or her representative, the Governor-General, is not to venture into Parliament grounds uninvited, or without good reason. On the occasion that a Sovereign entered the House of Commons in London, 368 years ago, Charles I was at the head of an armed guard, intent on arresting several Members of Parliament. A few years later, after a bitter civil war, Parliament executed King Charles.

These grounds, here in Aotearoa New Zealand, are also the home of the Parliamentary Library but in addition to having books and periodicals sent to me at Government House, I have, with the kind permission of the Speaker of the House, been able to enjoy, regularly, its historic ambience and its wonderful collection of periodicals and books.

That a legislature might restrict access to its library is not unique. I understand that when the United States Library of Congress was established in Washington DC in 1800, not even the President or other members of the executive were accorded right of entry to it.

The heart of that institution in the United States, after British Army invaders had burnt the Capitol in the War of 1812—and with it the congressional library - was the personal library of former president, Thomas Jefferson. However, while the heavily indebted Jefferson sold his library to the state, the institution whose 90th birthday we celebrate today was established by the gift in 1918 to New Zealand of a successful merchant named Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull.

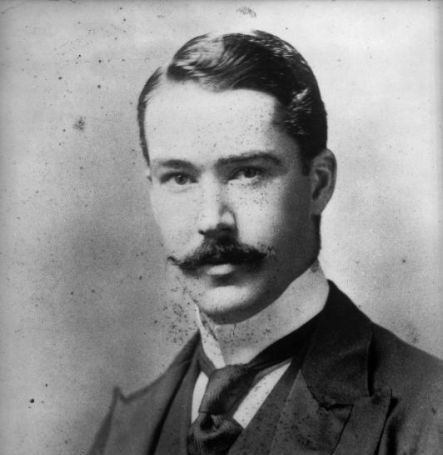

Turnbull was born in Wellington in September 1868, the youngest son of a local merchant Walter Turnbull and his wife Alexandrina. Turnbull was educated in Wellington and in London. He had no distinctive academic record and at age 16 began work in the London office of the family firm of Turnbull, Smith and Company. It was in this period that he developed the malady to which he later affectionately referred as “Bibliomania.”

In 1892, at age 24, he returned to Wellington and worked in the general merchants named W & G Turnbull, which had been founded by his father and later that year became a partner in the firm. With his father’s death in 1897 he took control of the firm, and retired due to illness in 1917 at the age of 49, a year before he died.

To New Zealanders of the present day, two things bear mention. The first is that in 1893 when he started collecting, Turnbull’s intent was upon acquiring, as it was put:- “anything whatever relating to this colony, or its history, flora, fauna, geology and inhabitants will be fish for my net from as early a date until now”

The handsome brick house, across Bowen Street, that bears his name, was his home for only a short time from 1916, it having been built especially by him to be a home for his ever increasing collection.

And what a mighty gift it was, comprising then some 55,000 books, along with drawings, prints, photographs, paintings, maps and manuscripts. Against this gift, donations by Sir George Grey to the Auckland City Library, and by Dr Thomas Hocken to the University of Otago Library, while significant, are by no means as large. The New Zealand Times described the Turnbull gift as being:- “The most generous bequest to the people of New Zealand ever made by a New Zealander since the beginning of New Zealand Time.”

But the reasons for Turnbull’s gift are not clear. While extremely well read and the member of several learned societies, Turnbull was not a scholar, publishing only a short monograph in his life.

The second codicil of his Will, which forms the first Schedule to the National Library of New Zealand (Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa) Act 2003, gives few hints as to his intentions, apart from directing that the gift should form the basis of a reference library in Wellington that was not to be broken up and which would be as it was put: “the nucleus of a New Zealand national collection”.

When his first Will was written in 1907 the original plan was to give his collection to what was then called Victoria University College. So the change, a few months before his death in 1918 to give it to the nation, may have reflected a concern, noted in a letter to the noted ethnographer Percy Smith, of New Zealand’s lack of national cultural institutions. The letter said in part:- “[the] important Australian States are supplied with these institutions by their governments who seem to recognise that beside the material welfare of the people, their mental welfare should also be provided for.”

Other clues, however, are provided in a 1912 letter of condolence to the brother of a Rotorua judge whom Turnbull had befriended many years earlier. Turnbull wrote as follows:

“The present day New Zealand public is apt to forget those who bore the heat and burden of the troublous times the colony passed through in the sixties’ and that is one reason why I strive to make my collection of New Zealand literature as complete as I can. Those who come after us will be discriminating enough, I feel sure, to blow away the mists of political chicanery that obscure the real history of the Dominion and to bring into view the men who really worked with their hands & risked their lives for the good of their country. My books & manuscripts, I hope will assist future searchers after the truth.”

These fragments suggest that Turnbull wanted to create a library that would be different from others. It would be a national institution and its role would not be in lending books to the general public, but rather operational as a fundamental resource for researchers, particularly for those delving into the history and characteristics of New Zealand and its peoples. An article in the New Zealand Free Lance expressed the matter in limerick form as follows:-

“Alec Turnbull’s a book hunter bold

Who lavishes leisure and gold

On pamphlets terrific

About the Pacific

And works on the Maoris of old”

While Turnbull’s aspirations were mighty, it would not be correct to ascribe, necessarily, any kind of saintly purpose. His view of “the truth”—and I place the word in quotes—would probably differ from that held by historians of today. The late Rotorua judge was a veteran of what were then known as “the Māori Wars” and as I have noted in an annual Waitangi Day address, New Zealanders continue to debate the ongoing ramifications of the violence and confiscations that went on in the mid-nineteenth century.

The legacy, however, of Alexander Turnbull’s gift remains. But in preserving that legacy, the seven Chief Librarians, from JC Andersen to Chris Szekely, have ensured that the Library has continued to grow and adapt. While the precious works in its collection, such the almost 900-year-old manuscript De Musica by Boethius, the oldest complete book in New Zealand, must be cared for in environmentally protected surroundings, that does not mean the institution should stand apart from the winds of change.

Like all public institutions, the Library has had its controversies. Some changes in the weather have been resisted, whilst others have been welcomed. The Alexander Turnbull Library, along with the National Library, is now based in temporary premises as work progresses to complete extensive repairs to the Molesworth St building which is due to be finished in 2012. Given the effect of the ongoing conservation project at Government House, due to be completed next year, I can empathise with the upheaval that such a major project can create.

The Alexander Turnbull Library has now established itself as a leading specialist research library. It continues to acquire important works to add to its collections, and its standing in the eyes of New Zealanders is reflected in the ongoing flow of significant donations of rare books and manuscripts to its collection.

In keeping with its statutory purpose to preserve, protect, develop and make accessible its collections, as it is said, “for all the people of New Zealand” it regularly organises significant exhibitions centred on its collections. In December 2008, I recall the privilege I had of opening exhibitions about the New Zealand artist Leo Bensemann and the English poet and polemicist, John Milton, curated by the Turnbull, while opening the National Library’s exhibition, Welcome Sweet Peace, to mark the 90th anniversary of the end of the First World War.

Even a cursory glance at the annual Turnbull Library Record and the Friends’ publication Off the Record, gives a hint of the diverse range of new knowledge that researchers have created. I understand that every year the Library assists some 25,000 researchers a year, with a third of those by means of telephone, email and post and the remaining two-thirds in person.

The availability on-line, which some call digitisation, of a large amount of material has allowed people from throughout New Zealand, and further afield, to access the Library’s collections. For example, the Library website Papers Past, now offers searchable content from one million pages of 58 New Zealand newspapers and periodicals from 1839 to 1932. This is an invaluable and growing resource for professional researchers and for genealogists investigating their family trees. This level of access and activity, belies suggestions that the Turnbull is an elitist institution as it is clearly meeting wide contemporary community needs.

In addition to research into New Zealand and New Zealanders, there has been significant work undertaken into the work of collections at the centre of the Library, such as the works of John Milton and others who form the foundation of the western intellectual tradition. The Turnbull collection of the works of Milton is, I am advised, regarded as one of the finest in the world.

This reference to Milton, the scholarly man of letters and an official serving under Oliver Cromwell, brings me to a final point. Milton’s major political works were written during the English Civil War and revolution of the 1640s and 1650s. During his 65 years he was a strong defender of the republican principles of the Commonwealth and of the regicide of the King Charles I, to which I referred earlier. He rejected the notion of the divine right of kings and argued that all men were born free. Milton’s legacy was well put by Benjamin Myers in his article in the Turnbull Library Record 2008, Milton’s revolutionary writings were written up in the following words:

“His works from this period contributed significantly to the emerging traditions of liberal political thought. Decades before Locke, Milton was vigorously advocating popular sovereignty, subjective individual rights, the separation of powers, the function of natural law, the right to religious toleration, and so on.”

Again, like Turnbull, one should, perhaps, be careful to not oversubscribe modern notions to Milton’s thinking. For example, I strongly suspect Milton’s views on religious toleration would not have extended to having a Catholic person representing the Sovereign in New Zealand.

However, research into Milton makes a deeper point. An understanding of Milton’s writings continues to inform our government, politics and constitution to the present day. The Restoration that followed the collapse of the Commonwealth established a new contract between the Crown and Parliament that underpins our arrangements to this day—the notion that while the Sovereign reigns, the Government rules.

Likewise, based on Alexander Turnbull’s own collection of manuscripts and artefacts, and subsequent acquisitions by the Library, research into New Zealand’s past continues to inform debate and discussion around the Treaty of the Waitangi.

It also informs an understanding of the fascinating people in the life of this nation. As an example, I mention Makereti, the book, by 2007 Founder’s Lecturer, Paul Diamond. This book, which made extensive use of the Library’s collection, brought to wide public attention the life of a woman, named Makareti Papakura who displayed tikanga Māori to a world audience, through her guiding of visitors to Rotorua.

This example demonstrates the important role of libraries, and particularly research libraries, in informing and underpinning public debate, which is at the heart of a democracy. While the right to vote is fundamental to a democracy, it is a shallow right when those casting their ballots may be illiterate or lack the information to form and debate opinions. It is not without good reason that no sooner have many totalitarian regimes taken over the media and other parts of the State that they have been known to begin culling the contents of libraries.

Libraries then are more than simply repositories of information, or, as they were infamously described by a 19th Century British politician, Herbert Samuel, “thought in cold storage”. Rather than being anything like thought in cold storage, libraries are, instead, as national institutions, fundamental pillars of a working democracy as vital to its health and wellbeing as a free press. Access to libraries is about more than improving one’s individual prospects. Access to libraries can equate to a fundamental human right to be as cherished as the right to freedom of speech.

The United States President Franklin Delano Roosevelt eloquently stated as follows:

“Libraries are immediately and directly involved in the conflict that divides our world, and for two reasons; first, because they are essential to the functioning of a democratic society; second, because the contemporary conflict touches the integrity of scholarship, the freedom of the mind, and even the survival of culture, and libraries are the great tools of scholarship, the great repositories of culture, and the great symbols of the freedom of the mind.”

It is, Ladies and Gentlemen, thus, on a note that salutes the role of libraries, and the role of this library and its founder, Alexander Turnbull, that I will now close, and in New Zealand’s first language offering everyone present greetings and wishing everyone good health and fortitude in your endeavours.

No reira, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, kia ora, kia kaha, tēnā koutou katoa.