No Laughing Matter - Privacy Awareness Week

May I begin by greeting everyone in the languages of the realm of New Zealand, in English, Māori, Cook Island Māori, Niuean, Tokelauan and New Zealand Sign Language. Greetings, Kia Ora, Kia Orana, Fakalofa Lahi Atu, Taloha Ni and as it is the evening (Sign).

May I then specifically greet you; Marie Shroff, Privacy Commissioner, and your predecessor Bruce Slane; Cartoonist Chris Slane; Distinguished Guests otherwise; Ladies and Gentlemen.

Thank you for inviting my wife Susan and I to be at this function and for me to launch No Laughing Matter? the Chris Slane Privacy Cartoon Exhibition marking and celebrating Privacy Awareness Week.

I will undertake that launching in, hopefully, an acceptable fashion in just a moment and just before doing so, would like to frame my contribution in a New Zealand setting. This is in two parts - the first registering a connection with the main players this evening. I am a long time regular Chris Slane cartoon consumer and have no fewer than three in a cartoon collection on my office walls. They each tell a story underpinning the fact that I have known Chris since he was a schoolboy and I continue to admire his ability to galvanise serious thought with good humour. Next, I have long term professional and personal associations with Bruce Slane and Marie Shroff. Part two of my framing is to speak a little about the concept of privacy in the age of the internet.

It is just 20 years since New Zealand's first link to the Internet, between the University of Waikato and the University of Hawaii, was established. But in that short space of time, and particularly since the mid-1990s when the commercialisation of the Internet began to gain momentum, there seems to be almost no part of our daily lives that has not been touched by this revolution in information technology.

The importance of the Internet was, in my view, accurately summarised recently by United States cyber-commentator John Perry Barlow saying: "With the development of the Internet...we are in the middle of the most transforming technological event since the capture of fire. I used to think that it was just the biggest thing since Gutenberg, but now I think you have to go back farther."

As this comment suggests, we are only part of the way on that journey. I suspect that we may be merely at the end of the beginning. It will be in the 21st Century that the full implications of the digital age will become apparent and we will find out, as one science fiction character wryly noted, "just how deep the rabbit hole goes".

We all know how the internet and IT equipment have changed our working lives as well as our private lives. There will be those among us who can, recall saying things like: "How did we ever survive without the fax machine?" Now, as we know, the fax machine is largely a lonely piece of equipment that sits in the corner gathering dust and startles everyone on the odd occasion that it unexpectedly starts hooting.

The transformation that the internet has wrought has been largely positive. We are more connected than ever before. With devices such Blackberrys and Iphones, we can literally carry a computer in our pocket. Emails and text messages can be sent and answered, the internet can be surfed and phone calls can be made at anytime and in almost any place. How things have changed since a writer in Popular Mechanics forecast 60 years ago that: "Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons"!

But the internet has also provided a new means for criminals to defraud unsuspecting consumers or for unscrupulous retailers to sell defective goods. By spreading computer "viruses," "worms" and "trojan horses," hackers can not only damage our systems but steal the information they contain. That information could be credit card details, PIN numbers or damaging personal information. They can literally steal our identities.

As well, the information we provide through electronic transactions or through online surveys and promotions, provides considerable information about ourselves such as shopping habits that we might not want others knowing about.

The internet has allowed governments to more efficiently and effectively provide services and information to its citizens. But it has also allowed governments to not only store enormous amounts of data about us, but also to cross-match it in ways that were never envisaged when the information was provided.

Early concerns about the use of electronic technology particularly focused on the ability of governments to misuse the information. On this last front, New Zealand was a leader in managing the government's access to and use of sensitive personal information stored electronically. When it decided to construct the former Wanganui Computer Centre, Parliament passed a law in 1976 to oversee this powerful new tool.

The legislation, in its preamble, recognised that privacy was a balancing act. Key law and justice agencies would be given shared access to the system so they could more effectively carry out their work. But Parliament specifically stated that law would also "ensure that the system makes no unwarranted intrusion upon the privacy of individuals." Parliament recognised that by establishing the Centre, there would be some intrusion into individuals' privacy, but that that intrusion should not be unwarranted.

Thirty-three years later, our understanding and expectations of what may "unwarranted" continues to evolve and is a grey area. As American science fiction writer David Brin once wryly noted: "When it comes to privacy and accountability, people always demand the former for themselves and the latter for everyone else." This kind of point is inimitably made in Chris's cartoon in the exhibition where a man pushes through a crowd gathered around a person who has collapsed: "Let me through", he exclaims "I have a morbid curiosity"!

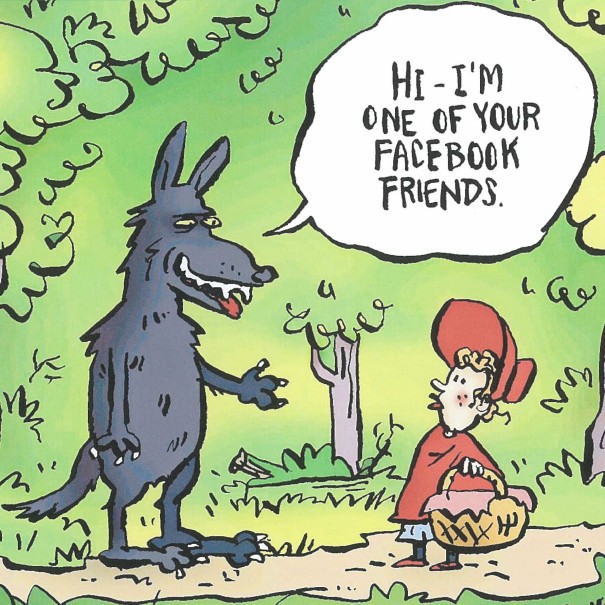

Likewise, our expectations and laws continue to evolve at a pace that lags far behind technological innovation and advance. When Parliament passed the Privacy Act in 1993, applying key privacy principles to all agencies, both public and private, the internet was largely the preserve of university researchers. Few would have envisaged that today a social networking website such Facebook could have more than 200 million active users worldwide, sharing 1 billion pieces of content every week.

What does this mean? While organisations such as Privacy Commissioners have been established in many countries to create privacy codes and resolve complaints about breaches, the reality is that the real protection of our privacy lies in the community's own hands.

When we engage online, loading videos, photos or blogs that contain personal information, we should always consciously think about how far the information might go. Likewise, while we can have some control over our own personal computer at home and use software to remove viruses and other cybernasties, the wisdom of conducting internet banking on a public computer needs careful appraisal.

A good example of how careful we need to be can be found in research undertaken by Gehan Gunasekara and Alexandra Sims, both senior lecturers in the University of Auckland Business School. Their fascinating research into online competitions found considerable non-compliance and misunderstanding about the requirements of legislation designed to protect consumer privacy and prevent spam emails - another grey area.

Another piece of the leading edge in dealing with Privacy emerges from the current issue of The Week where it is reported that the European Commission is to investigate Britain's privacy laws on the grounds that they allow companies to to sell information about how people use the internet without their consent. In 2006-7 for instance British Telecom did not tell its internet customers that their web browsing habits were also being monitored by a company called Phorm. Phorm collects data about what people search for on the internet and allows BT to sell it to advertisers. Under British law it is legal to secretly intercept online information if there are "reaonable grounds for believing" that consent would be granted, so such companies currently operate in a grey area.

Returning to the Auckland research, it is a wakeup call about the need for members of the public to be wary about who they give personal information to, and also to make complaints to the Privacy Commissioner if standards are not being adhered to. It is also a timely reminder to businesses and all organisations that maintaining good privacy standards is not just a legal requirement but also good business. Consumers who start receiving unwanted emails, not only from the company running the competition, but many others as well, are hardly going to look favourably on that business.

To that end, I wish to congratulate Privacy Commissioner Marie Shroff, her predecessor Bruce Slane, and the staff of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for their ongoing work in promoting a culture in which personal information is protected and respected.

Both of you two Commissioners have taken an approach that while waving the big stick has its place in dealing with flagrant breaches, it is in setting and maintaining privacy standards that the community will derive most benefit. And like any community issue, the answer will have come from within. The Privacy Commissioner's Office has also realised that in today's connected world, where millions of voices are clamouring to be heard, it is necessary to be innovative to capture the public's attention.

This is why the Chris Slane exhibition is so worthwhile because it engages on a number of levels. Having looked at the cartoons, there is no doubt about how funny they are. But by using humour, the exhibition engages people from all walks of life with language and concepts we can all understand. Conferences and workshops are great for specialist audiences, but they will rarely, if ever, reach a wider audience.

And I cannot think of a better cartoonist than Chris Slane to bring together such a collection of art. Chris' work, which has received many awards, stands in its own right. As the son of our country's first Privacy Commissioner, Bruce's work no doubt was a catalyst. The result is our general good fortune.

For these reasons it thus gives me great pleasure to declare the Chris Slane Privacy Cartoon Exhibition officially open.

And on that note, I will close in New Zealand's first language Māori, offering everyone present greetings and wishing you all good health and fortitude in your endeavours. No reira, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, kia ora, kia kaha, tēnā koutou katoa.

For more information about Privacy Awareness Week, click here.